BRUXISM, what can we do on it?

Nowadays there are a lot of people in our society who are suffering from bruxism due to several factors. The Bruxism is a parafunctional activity of the masticatory muscles grinding or bracing the incisor and molar teeth. This activity occurs normally during the night (Thorpy 1990, Lobbezo Et Naejie 1997) and also could take place during the day (Marbach et al 1990, Lobbezoo Et Naejie 1997, Marie Et Pietkiewicz 1997). This parafunction could get worse under certain conditions.

On the other hand, although the Bruxism is considered as a parafunction that means a disordered function which implies bad condition with negative effects, could we be sure that the Bruxism does not contribute with any important positive physiological functions such as facilitating the air-flow obstructed during sleep?

Exists some literature which suggest that The Bruxism plays also a supposed positive role in this direction (Lavigne et al 2003).

In view of the above arguments, a fair defenition of Bruxism is a repetitive jaw-muscle activity characterized by clenching or grinding of the teeth and/or by bracing or thrusting of the mandible. Bruxism has two distinct circadian manifestations: it can occur during sleep (indicated as sleep bruxism) or during wakefulness (indicated as awake bruxism). (Svensson and Winocur. 2013).

Physiolocigal mechanism of dysfunction and pain

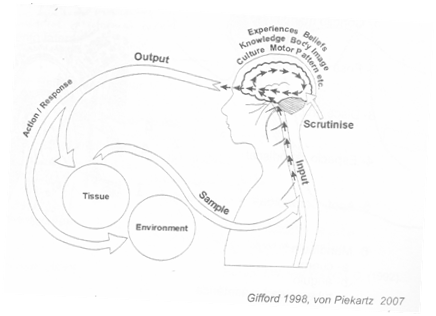

A part from the concepts mentioned before, it is important to understand something about the pathobiological mechanisms of dysfunction andpain and body reactions through The Mature Organism Model (MOM), in order to have an easier understanding of what happens when people suffer from Bruxism.

The Pathobiological Mechanism is composed of:

• Input pain mechanism

• Processing pain mechanism

• Output pain mechanism

These mechanisms develop several responses and symptoms due to different biological influences in each one of them. Lets discuss the mechanism first shortly before we discuss Bruxism further

Firstly, Input mechanism is the afferent information going up to the Central Nervous System (CNS) due to a damaged tissue or harmful environments. Then, the pain response is made by the peripheral nerve outside of the dorsal horn and the brainstem.

Secondly, if the stimulus arrives to the CNS, then there is a mixture between the peripheral information with the central information which is based on emotional and cognitive factors, motor patterns, culture, knowledge, experiences, beliefs, etc… This is the Processing Mechanism (central sensitization).

Finally, the Output Mechanism is the efferent information which affects the response. The output symptoms are conditioned by the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system, the motor system, and the neuroendocrine and neuroimmune systems. The Output Response depends on the input, the central processes and one of the most important factors: the time.

How can Bruxism been classified within the pathobiological Mechanisms?

After shortly explaning the pathobiological mechanisms we could say that bruxism is an output motor function activity or an output parafunction activity depending on the literature, as we have described before.

The diagnosis of Bruxism is not easy. Dentistry sometimes, not always, focuses on teeth attrition. But the evidence of attrition does not necessarily indicates a current bruxism problem. Furthermore, attrition cannot always be discriminated from erosion and abrasion. A relative new measurement establishing with reasonable certainty whether a person may suffer from bruxism is called polysomnography (Lavigne etal 2008) or (intramuscular) electromyography (Abe et al. 2012).

Whereas the sleep bruxism should be based on self-report, a clinical examination, and a polysomnographic recording, preferably along with audio/video recordings, the awake bruxism should be based on self-report, clinical examination and an electromyographic recording, preferably combined with momentary assessment methodology, which permits a true estimate about the frequency of tooth contacts during wakefulness.

Sleep Bruxism

Research show that 60% of people with sleep disorders (mainly in the superficial sleep phases, during Stages 1 and 2 of the sleep cycle and to a lesser extent during rapid eye movement ‘REM’ sleep) (Dao et al 1994, Kato et al 2003, Lobbezoo et al 1996) are affected by the rythmic masticatory muscle contraction (Lavigne et al 1995), and this is the only well known direct cause. But the experience of therapists treating people show us that there could be other factors influencing on the appearence or the persistence of the Bruxism.

A case–control study design was used with the focus on genetic factors connected with the metabolism of serotonin – a neurotransmitter believed to play a role in the aetiology of bruxism (Winocur et al 2003). (Abe et al. 2012) the authors concluded that genetic factors could contribute to the aetiology of sleep bruxism. Furthermore, other studies also concluded that Bruxism appears to be partially genetically determined (F. Lobbezoo, C.M. Visscher, J. Ahlberg & D. Manfredini. 2014).

Are People who suffering from Bruxism conscious about it?

Different studies support that only conscious in a 10-20% of human beings (Carlsson & Magnusson 1999). The incidence decreases with age, especially beyond the age of 50 (Dao et al 1994). There is a positive correlation between bruxism, lip-cheek-nail-biting, and craniofacial dysfunctions and pain (Kieser &Groeneveld 1998, Widmalm et al 1995). Only 17–20% of patients with bruxism may suffer from pain and dysfunction (Goulet et al 1993).

Some thought about subjective Examination

As a specialized physiotherapist in the orofacial -cranial , next questions may be suggested which may be usefull for further assessment and management

• Experiencing tooth ache on waking.

• Feeling physically tired due to a disturbed sleep

• Neck pain on waking, usually combined with one or more of the above mentioned symptoms

• Perception that the masticatory muscles are stiff and tense and the masseter muscle is ‘tired’ on awakening

• Wakes during the night because of the grinding sounds and/or their partner is aware of them grinding

• Muscle tiredness during the day which is associated with jaw function

• Wakes with a locked jaw or soreness of the masseters and temporalis (modified after von Piekartz 2009)

From literature, a heap on contributing factors which may interference which each other and may support long term Bruxism with or without complains:

• Cognitive and emotional influences such as extreme stress, anxiety, discontentment and frustration.

• Affective and cognitive influences developing changes in autonomic and motor outputs.

• Psychological and emotional influences related to processing problems.•

• The posture.

• Oclussal dysfunctions such as Retrognathia, Prognathia or a Crossbite occlusion which require dental assessment.Ç

• The absence of one or more teeth that changes the occlusion and, moreover, the masticatory muscles activity.

• Abnormal craniocervical, facial, and mandibular morphology in the head, face, and neck regions. Face Asymmetries

• Craniomandibular, facial and dental dysfunctions such as malocclusion or TMJ disc displacements are considered to facilitate an abnormal interactive bone tension (stress-transducing). The environment and Sleeping disorders mentioned before.

• Face or Cranial Trauma

• Persistance orofacial painful region

Is Bruxism a diagnosis which may be influenced by specialized physical therapists ?

Bruxism can be treated by Crafta’s manual techniques after doing a good and structured assessment of the dysfunctions, symptoms, contributing factors and pain mechanism. Crafta’s therapists use muscles tissue, cranial and Temporo-mandibular techniques, and moreover exercises for reeducating this parafunction combined with occlusal treatment, psychological intervention and Behavioral treatment. Also the patient could need some medication for the pain.

The main intervention is based on:

• Pain management exercises.

• Education and behavioural interventions about pain, symptoms and dysfunctions in order to reduce the parafunction in itself, and to understand also the mechanism of pain and dysfunction like Habitual Reverse Technique.

• Muscular treatment to relax them applying stretch and Trigger and tender points techniques and to control the special nocioception.

• Cranial, facial, cervical manual techniques in order to change the stress transducer forces in the cranium.

• Treatment of Temporo-mandibular Joint dysfunctions.

• Miofeedback training.

• TTBS exercise to enhance teeth, tongue, breath and swallow functions.

• Propioceptive stimulation.

• Coordination exercises.

• Exercises to change the posture.

• Evaluation and Education to have better daily habits

• Cooperation with dentists to assess if the patient needs to wear a splint or the patient needs some dental treatment.

• Cooperation with sleep disorders specialists.

• Cooperation with psychologists to treat affective problems or emotional disturbances.

In conclusion, there are many and different origins that maintain and produce Bruxism known as a continued contraction of the masticatory muscles. It is not exactly clear all the contributing factors for this parafunctional activity, but the most important factors are: stress, occlusal dysfunctions, psychological and emotional influences, affective and cognitive influences, Cranial Assymmetries and sleeping disorders. It is also important to know the Pathobiological Mechanism of MOM in order to understand the multiple factors involved and that there could also be a partial hereditary influence.

GEMMA MANERO PONS

Physiotherapist, Kinesiologist and Crafta’s Therapist

Num col. 3545

References

• Von Piekartz H. Craniofacial Pain: Neuromusculoskeletal Assessment, Treatment and Management. Butterworth Heinemann Elsevier, 2007.

• F. Lobbezoo, J. Ahlberg, A.G. Glaros, T. Kato, K. Koyano, G.J. Lavigne, R. De Leeuw, D. Manfredini, P. Svensson & E. Winocur. Bruxism defined and graded: an international consensus. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation 2013 40; 2–4

• F. Lobbezoo, C.M. Visscher, J. Ahlberg & D. Manfredini. Review Bruxism and genetics: a review of the literature. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation 2014

• Von Piekartz H. Management of parafunctional activities and bruxism. Chapter Twenty. 2009

• Lobbezzo F, Van Der Zaag J, Van Selms MKA, Hamburger HL, Naeije M. Principles for the management of bruxism. Journal of oral rehabilitation 2008; 35/7):509-523

• Morse DR. Stress and bruxism: a critical review and report of cases. Journal of Human Stress 1982; 8(1):43-54

• Laat A DE, Lobbezoo F. Bruxisme: alom gekend, maar moeilijk te vatten. Ned Tijdschr Tandheelkd 2000; 107: 271-274

• Louis Gifford. Pain, the tissues and the Nervous System: A conceptual model. Physiotherapy Journal, 1998, vol. 84, nº1

Podeu consultar la versió original de l’article a https://crafta.net/index.php?route=news/article&news_id=50

Dejar un comentario

¿Quieres unirte a la conversación?Siéntete libre de contribuir!